From Marxist Revolutionary to Capitalist Brand

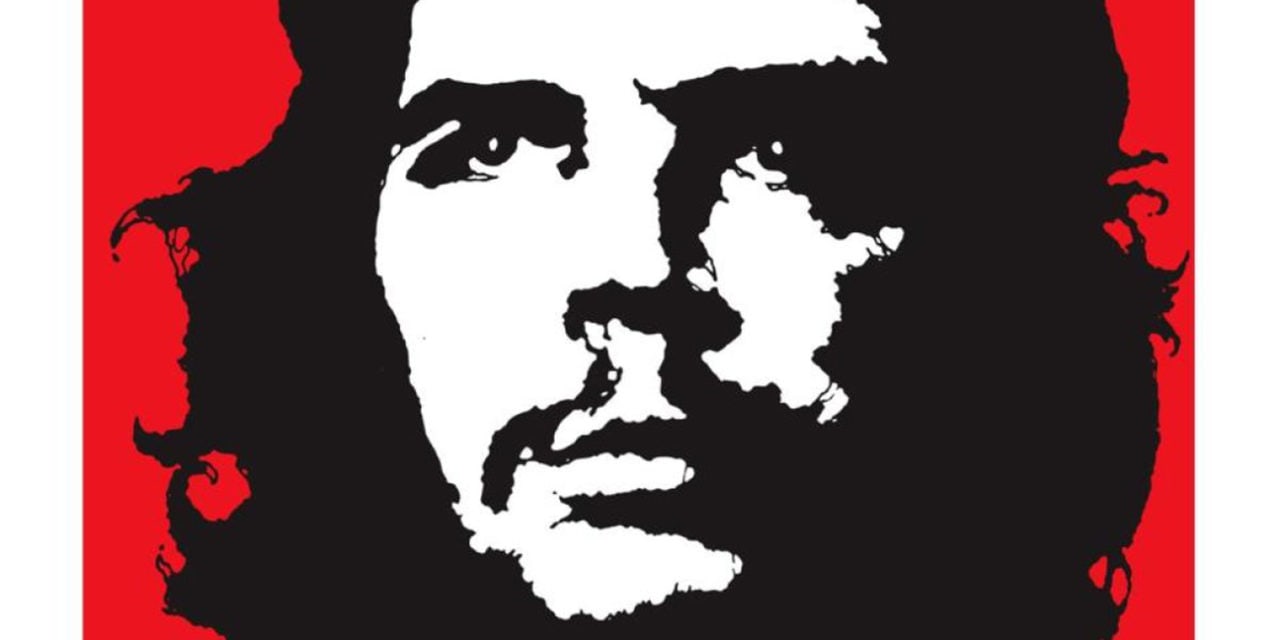

It is an image that has been cited as the most famous photograph of the 20th Century and, according to the UK’s Victoria and Albert Museum it is a photo that has been reproduced more than any other image in photography.

It has also spawned a multi-million dollar industry around the world with product lines ranging from T-shirts to diapers, bath foam and playing cards and has been seen adorning celebrities such as Liz Hurley, Lindsay Lohan and even Prince Harry.

More importantly though, Alberto Korda’s 1960 photograph of Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, entitled Heroic Guerrilla, and which was first published in 1967, was to turn the controversial revolutionary into a cultural icon whose popularity today around the world is as strong as ever.

The photograph and the subsequent classic graphic image by Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick have become symbols that frequently stray far from Che’s hard-line Marxist message. Ernesto Guevara, known as Che Guevara was born in Argentina in 1928. He was a politician, writer, journalist and Argentinian doctor but, of course, is best known as one of the ideologues and commanders of the Cuban Revolution (1953-1959). El “Che” Guevara was convinced of the need to extend the armed struggle throughout the Third World and he drove the installation of guerrilla groups in several countries in Latin America. He was captured and executed in Bolivia on October 9th 1967. Guevara remains both a revered and reviled historical figure that Time magazine called one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th Century.

It is ironic then that the Korda photo has become the basis of ‘capitalist’ activity that has seen Guevara catapulted from revolutionary to a major brand.

Interestingly, when the photograph was taken, it formed the basis of a very early ‘viral’ campaign. Korda was never paid for the photograph and the image has been cited as an example of the merging of politics and marketing.

For decades after it first appeared, the famous image was unhindered by international copyright agreements because Cuba was not a signatory to the Berne Convention. Fidel Castro described it as a ‘bourgeois concept’ and was eager to use Che to project an image of Cuba internationally. His attitude, and that of Korda was that the more the image was reproduced the more it drew attention to the cause, particular after Che’s premature death. Almost by accident, Castro helped Che go viral.

The same applied to the Jim Fitzpatrick silhouette graphic that was based on the photograph. The artist met Guevara in the early 1960s and believed in the Cuban cause. “The poster was my revenge for Che’s brutal murder,” he explained. “I felt he had been disassembled and would be forgotten. But he was a hero and a Marxist and I felt strongly that this shouldn’t happen.”

When the Cold War ended, Cuba began to see the benefits of joining the World Trade Organization and, as a result, embracing its rules on intellectual property. Cuba began to market itself as a nostalgic travel destination where musicians from the famous Buena Vista Social Club as well as artists such as Korda were used.

However, for forty years, the images were reproduced on countless products, unhindered by copyright and licenses. The original Guevara message became diluted and the image became a countercultural symbol for new generations of youth. Many had little or no idea what Guevara stood for. They just saw the image as a more generalised anti-authority statement. He became a pop-art icon

However, Korda, Fitzpatrick and Che’s family still believed in the cause and there came a point where they recognised that, in order to prevent products appearing that they believed were contrary to the beliefs, they had to formalise and control the brand.

Korda successfully sued a London advertising agency for using a version of his Guevara image in an ad campaign for Smirnoff vodka. Korda believe that, as Che didn’t drink, should not be associated with alcohol. He donated his $50,000 settlement to Cuban health care.

Following his death, his daughter began to aggressively enforce the copyright and successfully sued a number of companies around the world including a Mexican burger chain, a French perfume manufacturer and a Swiss maker of T-shirts. She also began to sell the rights to the image for Che-themed merchandise creating a new revenue stream and helping her enforce her copyright around the world. Fitzpatrick, whose concern was that revenues from products benefitted people in Cuba, donated his rights to the Guevara family in Havana. And Che’s daughter opened the Che Guevara Studies Centre in Havana with the express intention of containing the uncontrolled use of his image.

Today, whilst the original ideology may have been diluted, the iconic image is still popular around the world. French lawyers, Euro Legal Counsel Group represent Korda’s estate for licensing worldwide and have appointed Biplano to represent the brand in France, Spain and Portugal.

As proof, if it is needed, Amazon features more than 5200 Che products ranging from books and T-shirts to posters, jewelry, clocks and watches, calendars and more. Ebay, too, has nearly 8000 Che-branded products on sale covering all aspects of apparel and accessories as well as publishing and giftware.

Fashion Victim’s Che range in 2005 was responsible for a substantial portion of their $5 million sales and thechestore.com, established in 1999, carries the largest collection of Che Guevara merchandise with ranges including apparel, audio and video, dolls and figurines, clocks, cups, flasks and glasses, lighters, stamps and books.

Despite popular revolutions falling off the political radar in recent years, Guevara continues to enjoy great popularity around the world fifty years after his death. His is one of the few images that has retained popularity unaffected by fashion or trends.

And how would Guevara view his transformation from Marxist revolutionary to an icon of radical chic?

We can only begin to imagine…